Educators value the success of all students. Educators care for students and act in their best interest.

Before reading any of my pages on the standards, please visit my preamble of BCTF’s Professional Standards through the First People’s Principles of Learning, here.

This standard, neither supposes nor denies that valuing student success might look different for each student, or that the interest of each student might vary. It does claim, however, that whatever shape student success takes, it is the responsibility of the educator to value it. Thus, principle four, about acknowledging the roles and responsibilities involved in learning between generations, strongly relates to this standard.

Learning Principle 4: Learning involves generational roles and responsibilities.

In Indigenous culture, “rather than age alone dictating the designation of ‘Elder’ or ‘Knowledge-Keeper'”, it is understood that an Elder/Knowledge-Keeper is “a knowledgeable person who understands things that need to be learned by younger generations” (Chrona). I think the same thing is true for White, Anglo-Saxon, Protestant (WASP) traditions, where we identify persons with areas of expertise, and we go to them when we need to learn.

Photo from Pexels by Steffen Rühlmann

A point that becomes tricky with educators, though, is the habit of many to presume that educators are owed respect, or obedience from their students because of their superior age, which we take to be accompanied by knowledgeable experience. In truth, I argue that this respect is owed to the relationship shared between parties. “Elders/Knowledge-Keepers often notice when a teaching needs to happen based on the needs of the learner” but only “if there is a relationship established” do they “then move to help the learner” (Chrona). This is why it is so important that educators genuinely value students’ success, care for them, and act in their best interest: it builds a relationship. This relationship is also one of the key things underscored in principle four.

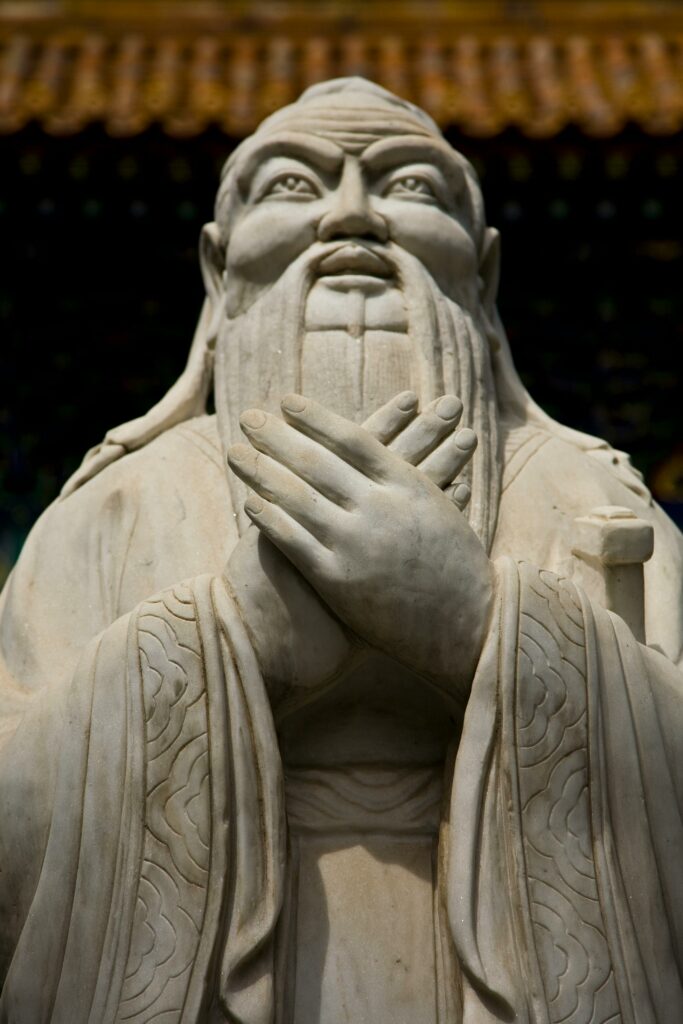

Standard one positions educators in a power relation with students, where the educator has a responsibility to value and care for students, and we don’t see the reciprocity. The fourth principle speaks to this reciprocity, though. Standard one reminds me of the five human relationships in Confucianism in ancient China. According to ancient Chinese Confucianism, there is the relationship between:

- Ruler and subject

- Father and son

- Husband and wife

- Elder and junior

- Friend and friend

According to the relationship, people in different situations could know how to behave to preserve harmony. For example, a husband is superior to his wife, and the wife, as a mother, is inferior to her sons, but superior to her daughter, who is inferior to all in her family, except if she had another younger sister. In this system, there is always a power differential, with one party member the superior of the other. In this system, though, the power of the superior member is also a responsibility.

Photo from Pexels by Charl Durand

In ancient China, the person with the privilige, is also charged with the care of the less privileged. This is like the dynamic of a teacher and student according to standard one. The educator is meant to have the interest of the student at heart, without reservation. So, the student is meant to obey the teacher without reservation, because it is what is best for them. Of course, systems of power are often abused, and for most of us, the student is placing to must trust in the fallible educator. We know, it is not the case that every teacher, in every moment, has at heart the best interest of their students, especially as they juggle the interests of up to 30 students! Regardless, in this dynamic of power lies the underlying philosophy of balance that underpins the filial system of ancient China: when each upholds their duties in the relationship, all is harmonious, for all. Hence, the importance of knowing and respecting that with power comes responsibility.

With great power comes great responsibility

Uncle Ben from Stan Lee’s Spiderman

Photo from Pexels by Deniss Bojanini

In truth, the person in the position of power only has their power thanks to the relative position of the other to them. If you’ve seen Disney Pixar’s a Bug’s Life, you’ll perhaps recall that the grasshoppers need the ants. Strictly theoretically speaking, if the grasshoppers had engaged in a more reciprocal relationship with the ants, treating their inferiors with due respect, then the ants would never have known the need to rise up against the grasshoppers, and neither the grasshoppers nor the ants would have had to do without. Moreover, the respect of the grasshoppers would warrant the respect of the ants.

Finally, principles 7 and 8 are also supporting this standard. Since valuing the success of students and acting in their best interest involves teaching and practising patience, as well as giving and taking time.

Learning Principle 7: Learning involves patience and time.

As for principle 8, the exploration of one’s identity is in the student’s best interest, and not only allows them to connect to their larger learning community, but also provides an opportunity to learn about their weaknesses and strengths and how to navigate the world effectively with them.

Learning Principle 8: Learning requires exploration of one’s identity.