This part of my page needs to be written in French & English, the two languages I am fluent in. Francophonie as a concept doesn’t exist in a singular English term. It is often mistranslated as meaning “French-speaking” but really, it means something more like identity of the french-speaker. I must acknowledge that I am not a francophone in many ways, since much of my identity is tied up in being bilingual, and speaking French and English, rather than having a French identity. Thus, if I were talking to you in English, I’d call myself a bilingual francophone, and if I were speaking to you in French, I’d call myself a bilingual anglophone. Which is why this page will be in both languages.

Je parle la langue francaise depuis que je puisse parler. Ma mère parle toujours le francais, avec un accent acadien, alors que mon père la largement perdue au fils du temps. Je suis très fier de pouvoir parler une deuxième langue mais surtout, je suis appréciatif de la perspective qui vient avec l’expérience d’avoir deux vocabulaire pour parler d’un seul monde.

Des perspectives croissantes!

Photo from Pexels, by Christina Polupanova.

Essentially, I want to articulate the point that the words we use, and the way we use them, is part of meaning-making and sense-making in the world. This is a perspective that is easily accepted through logical avenues, but which is not a lived reality for most English speakers who are monolingual. On the other hand, anyone who speaks more than one language has the opportunity to experience, first-hand, how the way we talk about things, and the words we use, shapes the way we find and make meaning and sense in the world. I am, therefore, extremely grateful that I was able to learn a second language.

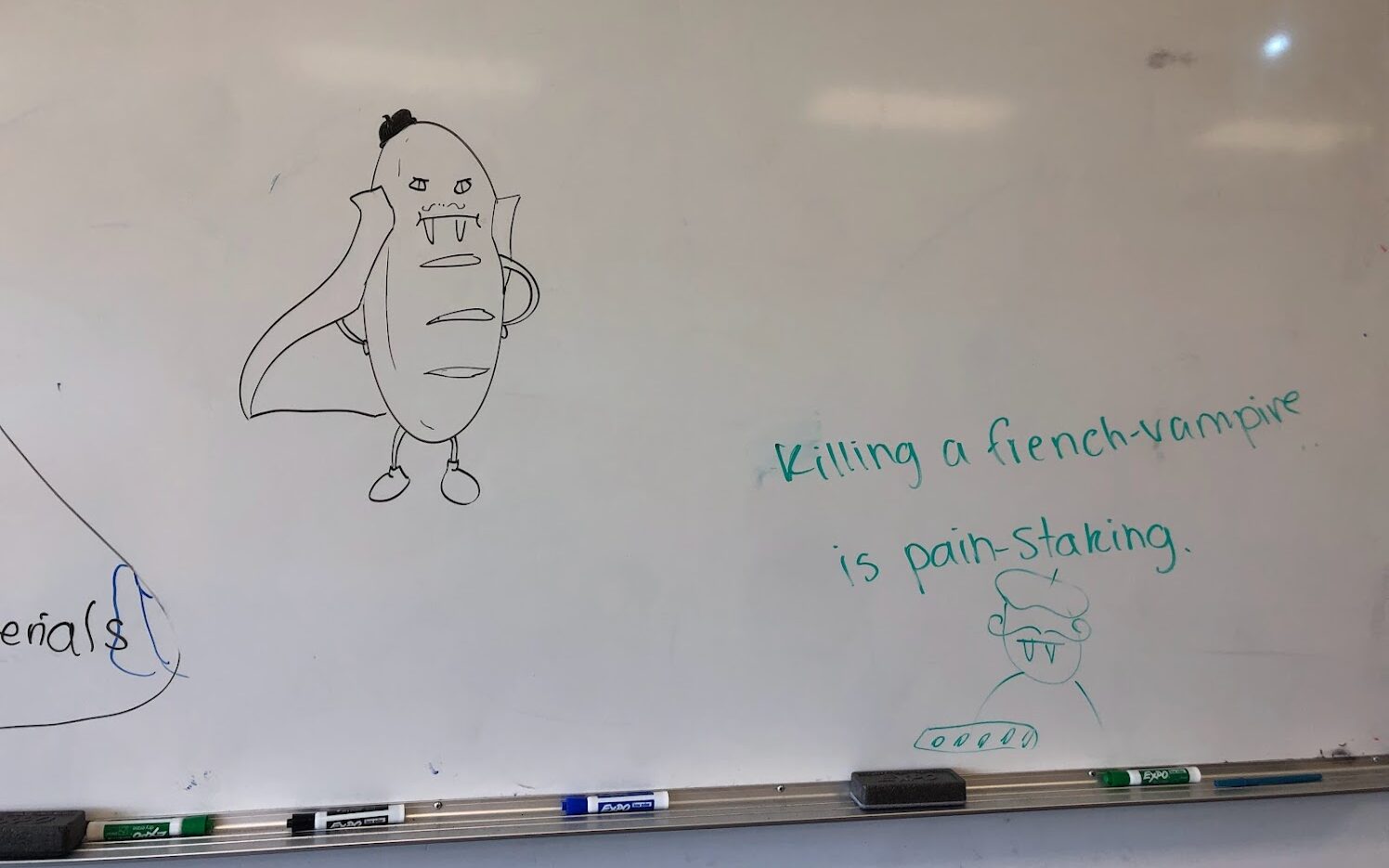

Photo par Isabelle Côté. Art par un.e élève de la programme francophone à École Duchess Park.

Malheureusement, mon français n’est pas ancré dans la culture ou même dans la famille dans une manière qui me fait ressentir une héritage française. Je reconnais qu’il y a des aspects de ma vie qui sont liées et mêmes véritablement changé par ma famille québécoise, acadienne, et franco-albertain. Pourtant, je n’est pas autant vécu cette identité comme hérité de jour en jour, mais articulé en certain moment, et absent dans d’autres. Néanmoins, je suis reconnaissante du privilège et responsabilité de pourvoir parler une deuxième langue. Ainsi, je ne déshonorai pas ce cadeau en perdant ma langue, ou en refusant d’engager avec mes alentours en français, n’important quand l’opportunité se présente.

Another point I need to articulate, then, is that, even though English is the predominantly colonial language in Canada, with French people often identifying with groups who were discriminated against by the Canadian government, the fact remains that French, globally, is a colonial language. It has been used to harm, assimilate, and discriminate in imperialist projects, especially in Africa, India, the Caribbean and elsewhere, and I am more French than English. So identifying with my colonial roots, truths, and practices to do the decolonial work I need to do as a human being and an educator, requires uncovering a past that is dislocated and from the land where I currently reside, in British Columbia. Be that as it may, colonial projects do not discriminate between their voluntold subjects by language, even when they use language to discriminate their against them. Regardless of whether I associate with English colonizers, I associate with English decolonialism. I wonder, though, whether associating with French decolonialism, and learning more about French colonialism, would bring me closer to feeling francophone. After, nationalism is the tool of colonial empires.

En tout cas, j’espère pouvoir apprendre plus de langues pour pourvoir encore pousser les limites de mon point de vue. De plus, dans le contexte d’enseignement, je ressens en moi un grand plaisir d’avoir la chance de pouvoir partager, ce que je considère le plus beau de secret caché, connaitre plus qu’une langue. Je répète, pourtant, que je ne suppose pas qu’une langue quelconque soit meilleure qu’une autre, et je ne prétends pas qu’il y a de quoi de spéciale avec la langue française. Plutôt, ce sont les contextes culturels, peut-être familial, communautaire, ou même, tout simplement, des rêves, qui rend qu’une langue soit personnel pour un locuteur. C’est grâce à cette connexion qu’un locuteur peut non-seulement apprendre une langue avec plus d’aise, mais s’ouvrir à des points de vue auparavant méconnus. Malgré mon sens de déconnexion avec un héritage francophone, c’est grâce à mon désir de m’exprimer dans la langue maternelle de ma mère, et de mes grand-parents, dont j’ai toujours voulu plus me rapprocher, que je suis connectée avec la langue française. Quelle autre beau cadeau: d’avoir une langue qui semble tous pour nous, pour qu’on puisse mieux se connaitre.

Wilfred Côté et Antoinette Fontaine

Grandpapa et Grandmama Côté, avec moi.

Photo par Noëlle Côté

Denis Caron et Angeline Ross

Pépé et Mémé Caron, avec ma mère, Sophie Côté.

Photo by Isabelle Côté